Last Updated on January 29, 2025 by Bread and Circuses Team

Bob Dylan once sang: Steal a little and they throw you in jail, steal a lot and they make you king.

While its unclear whether executives of social platforms are Dylan fans, it is clear that they’ve taken his message to heart.

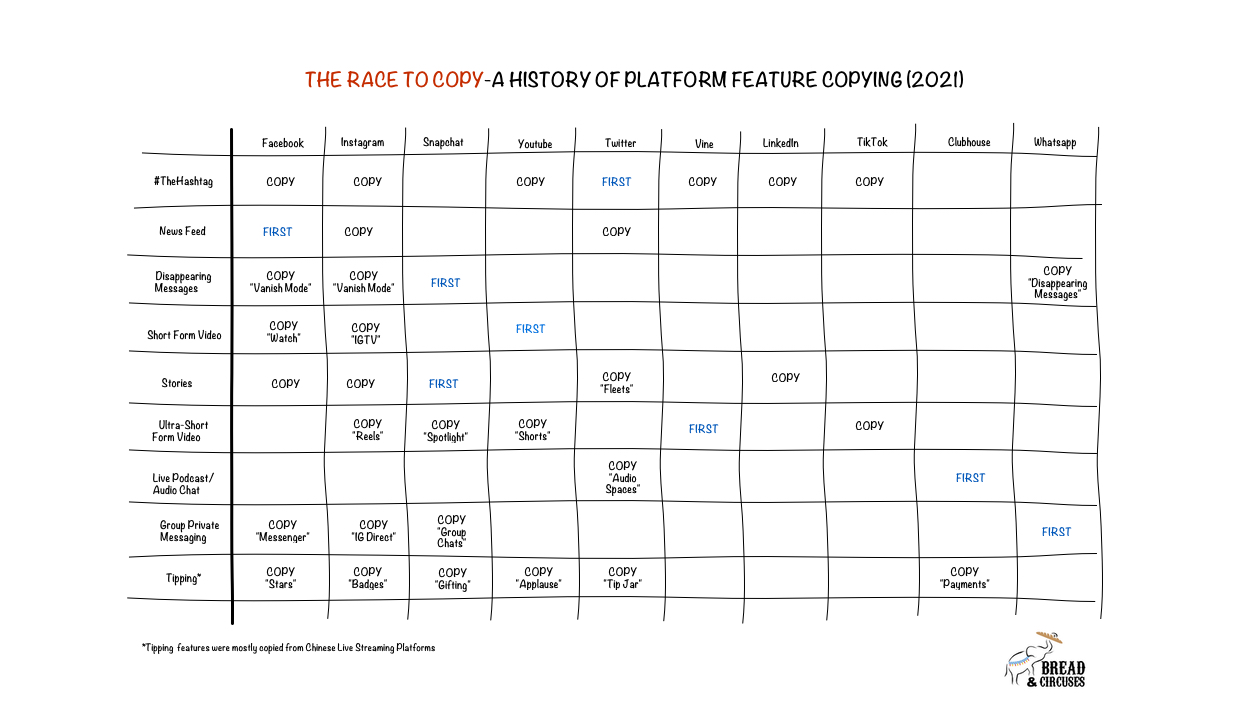

We’ve seen it repeated over and over again, starting in the early days of social media when emerging platforms like Facebook and Myspace copied basic concepts from Friendster (though much of Myspace’s growth is not attributed to copying, but rather a coding mistake), to Twitter’s hashtag copied by Facebook and Instagram, to Snapchat stories being copied by Facebook, Instagram and and even professional networks like Linkedin, to ultra-short form video now being copied by—what feels like everyone…even Youtube, who happens to already be a major video consumption destination, but who’s core product are videos that are, you know, just a little longer.

A social platform being a good copycat is not cheap imitation, it is a core product strategy. Though some copycat moves have been executed with tepid results, many have been wildly successful, leading to features that are now critical parts of the copiers platforms. “Stories” very quickly became a fundamental part of Facebook and Instagram’s growth: as early as 2018 (less than two years after its launch), Instagram stories had 400MM daily stories users to Snapchat’s 191MM. Now, over 500MM people use Instagram stories daily, posting over 1 billion stories.

So why, other than the obvious, is such thievery so fast-paced and rampant amongst Social Platforms? There are a few reasons:

Lowering switching value

Switching costs are used to describe barriers to switching to another product or service, whether that be financial, the time and resources it takes to switch, or some emotional inconvenience that comes from making a switch. Nespresso sells coffee makers at cost so that they can continue selling coffee, Apple has an ecosystem that contains all your media assets accumulated over time, Salesforce has a huge organizational learning curve, ATT and Verizon charge substantial termination fees if a user wants to exit a contract early. Switching costs are everywhere.

Social networks also have switching costs: Facebook has users logging notable life events such that the collective scrapbook of shared memories is a huge deterrent to “turning off” Facebook. On most platforms, Influencers would have to forgo a substantial fan/follower base if they were choose another platform of focus.

But in the case of social networks, “switching” is usually not a wholesale choice of one platform while deactivating an account on another, it is about switching attention. New features from other social networks are a potential threat to their piece of the attention pie. Users of an incumbent platform may prefer the expression that Tiktok videos offer, and therefore gradually spend more and more time on that platform at the cost of time spent elsewhere. Successfully copycating a feature lowers the threat of a switch to a competing platform, in this case not lowering a switching cost, but lowering a switching value.

“Transformed Consumer Contexts”

Moore’s Law is an observation that the number of transistors on a dense IC circuit doubles about every two years. It speaks to the exponential growth of technology, and since it was first posited by the co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductors in 1965, has been about right. These ever-tightening cycles on technological and product innovation have also been mirrored by ever-increasing consumer expectations from users about the technologies and services they use and consume.

In “Building the Agile Business through Digital Transformation” Neil Perkin and Peter Abraham discuss transformed consumer contexts, and particularly how, as products have become services, intuitive smart design and overwhelmingly good features are now mostly expected. In the case of social platforms, these consumer contexts are shaped in real time, and the lack of equivalent features very quickly shifts to a product deficit.

This creates an arms race between competing social platforms, as only the tallest are permitted to ride the roller coaster of continued user growth and attention. The launch of a new competitive product feature or introduction of a new competitor that finds a new way to engage an audience builds expectations of similar features elsewhere, and in these features, incumbent platforms find both threats and if copied quickly enough, opportunities.

In Media and Elsewhere, Opportunity and Growth Comes From Bundling and Unbundling, and Then Doing it All Over Again

As a serial repeater one idea that stuck with me over time was posited by Netscape/IBM/ATT’s Jim Barksdale: there are only two ways to make money in business: one is to bundle, the other is to unbundle.

Perhaps an exaggeration, but certainly a statement that for media particularly, proves true time and time again.

Whether it be verticalized websites being an unbundled version of newspapers, cable bundling television, streaming unbundling cable, blockchain potentially unbundling streaming (amongst other things). The cycle of bundling and unbundling has created new companies and cemented empires.

This is also true on a content format level. Take video and video lengths on platforms as an example. The biggest social platforms as public companies are under constant pressure to deliver continued financial results and therefore need to step outside of their native formats to attract users with different consumption patterns. Youtube, known as a TV/cable alternative and, being the world’s second largest search engine, a platform for intentional viewing, is looking for court less intentional viewer with Youtube shorts. At the same time, Facebook, the originator of the news feed and more transient viewing patterns, has been seeking to build intentional viewing through its focus on Facebook Watch.

These copied formats provide the tools for larger platforms to find new user and monetization opportunities. They are looking to bundle more and more kinds of consumption within their platform and gobbling up all formats and features makes users stick and advertisers spend.

It’s Good to be King…

With all of the reasons for incumbent platforms to be good copiers, one obvious question that arises is how major platforms should organize their product teams: should resources be dedicated to innovation, skunk works, and home grown platform enhancements, or should they be focused on intelligence and keen observation of social start ups globally, with developers at the ready to pounce on the next feature, a feature not new to the world, but new to their users?